Yet we have nearly 150 letters from Theoderic’s time that profess to be from his own hand, and come at least from the hands of those who served his will and heeded it most closely; we have transcripts of synods of the church that met under his direction; we have almost 300 letters from Ennodius of Pavia, the churchman with ambitions, who also wrote a grandiose panegyric oration in Theoderic’s honor, to sing his praises to his face and the faces of his court, and poems and other documents besides; we have letters from every pope who reigned in his time; we have the Book of Pontiffs recounting the deeds of those popes in short compass (and also the crucial part of the variant edition of that book done by the followers of the would-be pope Laurentius); we have the philosophical, theological, and autobiographical writings of Boethius; we have other fragments of panegyric orations in honor of his court, the chronicle of all the years of Rome made in honor of Eutharic, and a history of the Goths that was put together in Constantinople twenty-five years after he died but that depended somehow on the propaganda and learning of Theoderic’s last years. Considering the devastation that would strike his Italy in the decades after his death, and the long history of political disunity and disarray that would follow, the survival of so many books and artifacts of his time is a testimony to the ambitions of the man and to his posthumous good fortune.

Uppsala Gothic Bible

Other books survive to represent his court and its tastes: the Uppsala Gothic Bible has an obvious claim to our attention, but no less impressive is the elaborate and expensive manuscript, also coming from Ravenna and perhaps from the same book-producing house, of the Corpus Agrimensorum—the Collection of Surveyors. Magnificently illustrated, this manuscript brought together the technical treatises of the men who made possible Roman property management and Roman imperialism, the surveyors who put names and measures on the land and regulated a world of agricultural property for the benefit of the imperialists and their favorites. At approximately the same time, scholars at Theoderic’s court wrote about geography as well, and in the seventh century an anonymous writer admired Latin writers of this period for their learning, authors with the seemingly Gothic names Athanarid, Eldevald, and Marcomir bulgaria tour balchik.

Theoderic once had to settle a property dispute that called on the surveyors’ skills. The Chaldeans, he reminded his subjects, had discovered geometry, but it was the Egyptians who put it to practical use by marking out the lands that the Nile flooded each year. Augustus himself had, after all, ordered that the whole Roman world be surveyed and recorded in a census. “Today,” Theoderic said, “the surveyor’s art is far more popular than the other numerical sciences. Arithmetic has empty classrooms, ge¬ometry is for specialists only, astronomy and music offer knowledge for knowledge’s sake only. But the surveyors are the wizards who bring peace among men. You might think them crazed when you see them prowling the woodland in search of boundary markers, for the road is their book and they read it well.” Theoderic was every bit the Roman ruler in his patronage of these books and related arts.

Palace buildings in Ravenna

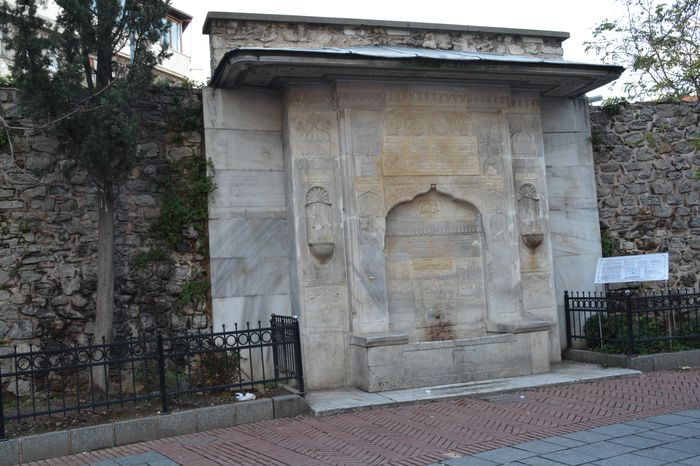

His buildings speak to us of him as well. Some we know indirectly from contemporary reports: palace buildings in Ravenna, Pavia, and Verona, with great sculptures of the triumphant monarch outside. In thirty years, Theoderic never finished the great palace he undertook in Ravenna, but every successor regime there used it until it fell to ruin long after. The pattern was entirely imperial, complete with a connection to the circus where the ruler could watch the horse races. You could see Theoderic on horseback in a portrait in the “Seaview dining room” (triclinium ad mare), and also standing between figures representing the cities of Rome and Ravenna over the grand entrance to the palace Christian emperors of the fourth and fifth centuries.

At Ravenna, he also restored an aqueduct built in Trajan’s reign, to ensure the water supply. Some of his work there survives more or less intact; one example is the church of San Apollinare Nuovo, which was Theoderic’s palace church. The original decoration included mosaic portraits of Theoderic and his court at one end of the south wall, by the entrance. They appeared at the head of a procession of saints, martyrs, and biblical figures, with an image of Christ at the altar end of the wall. (In later years, when Constantinople had seized control of Ravenna, clumsy mosaicists effaced Theoderic’s own image and others of his court, leaving just enough traces, including a ghostly shadow of the man himself, to let us see what they meant to destroy.) His buildings follow others equally impressive—like the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, the doughty princess and empress regent of the fifth century—and precede others, as we shall see. We can hardly differentiate Theoderic’s Ravenna from what went before or came after in its magnificence.